Worms, Lemons, and Ultraviolet Rays

- Liza Burton

How could a cloud itself ‘shiver’? A spectral image of silvery foam, reacting to its own weather system, in such a coarse and bodily way. Shiver with cold, fear or

ecstasy? I imagine a poisonous hemlock, shadowy in the night; or a scoop of lychee sorbet, still hardened with beads of frozen crystals, echoing in the sky. It's something like the practice of Forest

Bathing. Clouds and trees, vast and wild and unbounded. Our bodies drown in them and tremble with the precipitation.

“Forest Bathing” or Shinrin-yoku in its native Japanese, is rooted in ancient Shinto and Buddist ideals of harmonic balance between humans and nature, engaging the

five senses. The compounds emitted by trees and plants are healing. In Asia, the Hinoki Cypress and the Japanese Cedar emit phytoncides, which boost the human immune system. In Europe, oaks, beech,

birch and Hazel do the same. Hovering between our skins and pelts, smaller than a freckle and lighter than a strand of hair; micro and macro ecosystems are alive. They linger, always thirsty for

cedar wood smells, Cheeseweed Mallow, the candy caned Wunderpus. Material surroundings directly affect our minds, our nerves, our ‘parasympathetic nervous system’ (as forest bathing has been said to

do), but they also live independently and affect one another.

Kenji Lim is interested in the sticky relationships between the properties – the viscosity – of nonhuman lives. Gummy cleavers and goosegrasses are enmeshed with

radioactive waste and the threat of deep earth mining, sourdough starters fuse with meteor showers – there is an awesomeness to the spaces that exist outside of human subjectivity. A ‘dark ecology’

of things that, relative to humans, so vastly permeate time and space, it’s impossible to reciprocally engage with them. As theorist Timothy Morton defines, they are ‘Hyperobjects’,

“Hyperobjects are not a function of our knowledge, they are hyper relative to worms, lemons and ultraviolet rays, as well as humans”.

Lim’s practice indulges in this fantastical landscape of non-human economies. It looks towards the charged, obsessive magic and necromancy that we imbue upon our

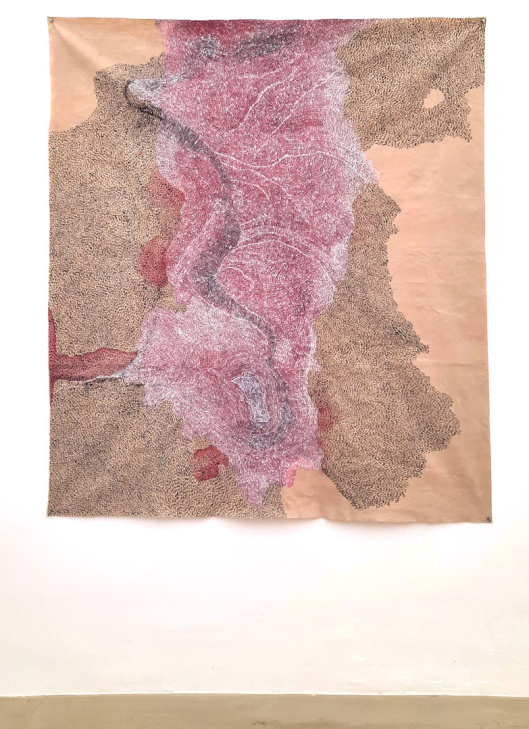

daily domestic surroundings, and then imagines the human untethering from this. Laps of pebbles and clusters of pigment hang and hold themselves together. Tissues and membranes embed and pucker at

unstretched canvas, leech-like. Ephemera Pooling, hot and light and dappled with byzantine purples. A horizon line with a magnet of blood orange pithiness.

The sense of liveliness in the intricate marks in Lim’s paintings creates a new material reality for the central sculpture. A Sleeping Beauty, coiled on the

floor of the gallery, abreast a soft carpet all of its own, probes its drowsy eyes from its iridescent cocoon, maybe blinking headily at the pixilated maps and drapery. Entwined in bioluminescence, A

Sleeping Beauty resists zoological definition. It plays with tendencies to bestow human emotions or physical sensations to the world around us.

Here, amid the feathery stratus and the mackerel skies and the labyrinthine sunsets, a social network of things exists. It is humming like the filament of a laptop;

a flicker between pixels. A Sleeping Beauty, at the centre of it all – a placenta – feeds heartily; growing lethargic as it digests, pleasured, satiated, distended.

A nod to the Brothers’ Grimm, The Beauty has woken up. It stumbles and unfurls towards a world of inky puddles, saplings, furs and Tanzanite slipperiness.

The exhibition is itself a deity; a self governed Kingdom of dandelion dust and settled pollen.

Sources:

- Timothy Morton, in Graham Harman, Object Oriented Ontology, a new theory of everything. (London: Penguin, 2008).

234

- Lucy Jones, Losing Eden, Why our Minds Need the Wild, (London: Penguin, 2020). 70